Investigating a footprint

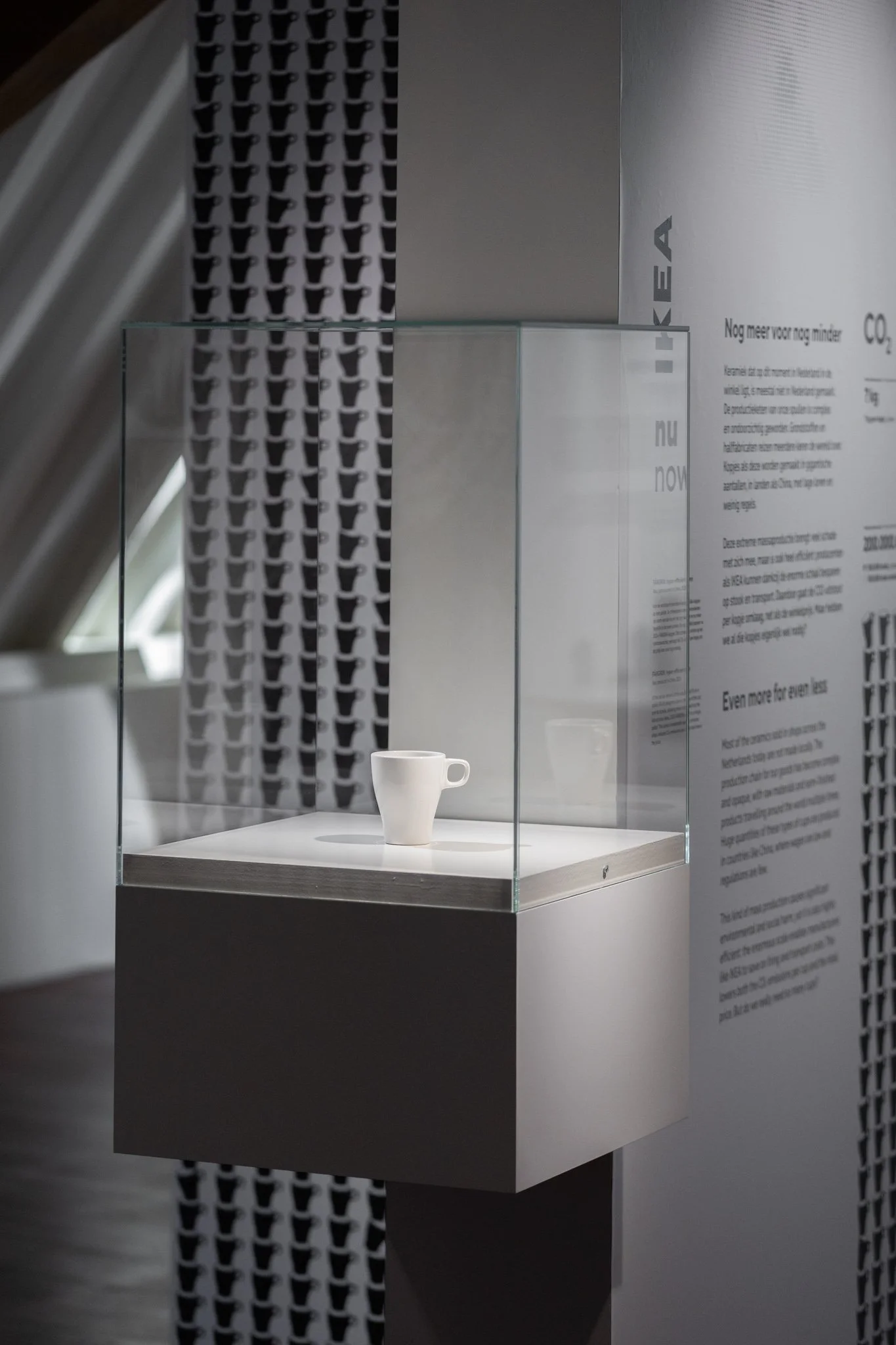

What does a coffee cup reveal about air pollution, raw materials, and social inequality? Ceramic is one of the most durable materials available: as long as it doesn’t break, it can last thousands of years. At the same time, the production is anything but sustainable. The firing process releases a large amount of CO₂, and some raw materials and glazes are harmful to humans and environment, or are running out.

The Princessehof National Museum of Ceramics and Lab AIR explore this paradox in Sustainable Ceramics #2: Investigating a Footprint.

Featuring work by, among others: Alternative Ceramics Supply (Australia); Hannah Rose Whittle and Benedetta Pompili of the Rijksakademie Tech Fellowship Programme, Amsterdam; Studio Lotte Douwes, Rotterdam; and Fabrikaat, Nijmegen. Next to our Smogware project Lab AIR’s research on hidden stories of mass production is shown.

We are happy to collaborate again with our heros SIVK for graphic design and Roel van Tour for a short and beautiful film.

The exhibition is open from November 22 until October 25, 2026. For the accompanying program, the museum is collaborating with Crafts Council Nederland, offering workshops and events that delve deeper into the subject.

More on our insta account and website of Princessehof Museum.

This project is financially supported by Van Achterberg-Domhof. Pictures by Princessehof / Aron Weidenaar.

Overview of Lab AIR’s Smogware project made in different cities.

Vanitas - or how do we produce 1 gram of smog dust?

On and between the tableware on this table, Lab AIR gives examples of human actions that produce 1 gram of particulate matter – the amount of particulate matter that an average resident of Rotterdam inhales in about ten years. For example, burning wood in a stove for 20 minutes emits on average as much particulate matter as eating cheese in 3 moths, or meat in 5 days.

Lab AIR calls this “still life” of objects their Vanitas, after the theme that was very popular among Dutch painters in the 17th century. Vanitas paintings offer a moral warning: food like cheese and fruit symbolises abundance and decay, a fallen cup refers to wastage and charcoal symbolises our finite life.

These classic elements and data are combined with elements which refer to the making of the tableware, topic of the next chapter in the exhibition.

Exploring the history

Using ceramics as tools for awareness of sustainability raises questions: what is the footprint of the precious porcelain, the medium we work with?

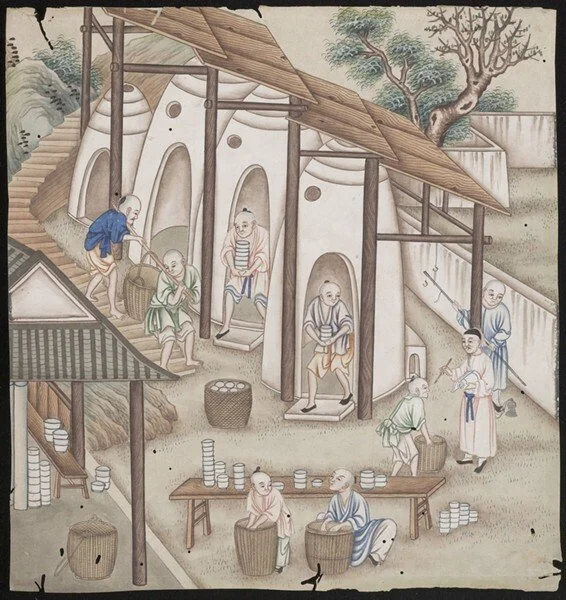

That question led to Lab AIR’s research. Four iconic cups, ranging from 16th-century Chinese porcelain to IKEA, represent key moment in the commercial history of ceramics in the Netherlands. Together, they show how ceramics have become a mass product - at the cost of depletion of resources and labour. The witnesses of the development of our economic and social system of breakdown.

With this exhibition, Lab AIR presents an exploration that invites visitors to think along with them. How do we see efficiency and profit? Should things be done differently, and if so, how?

Unloading the kilns in Jingdezhen, China.

Unloading the kilns in early 1900 in the factory of Petrus Regout & Co in Maastricht, the first industry in the Netherlands.

Pioneers

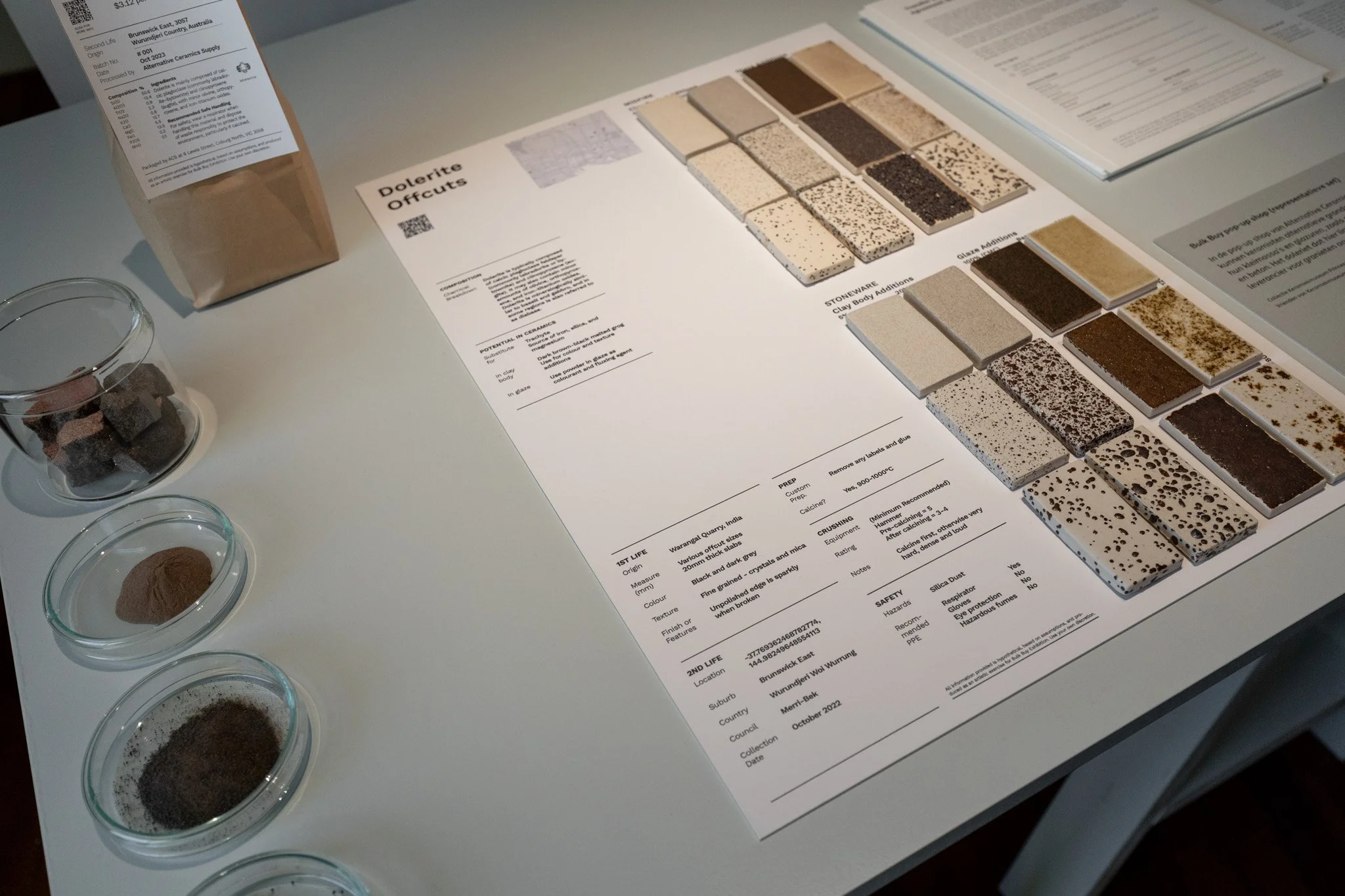

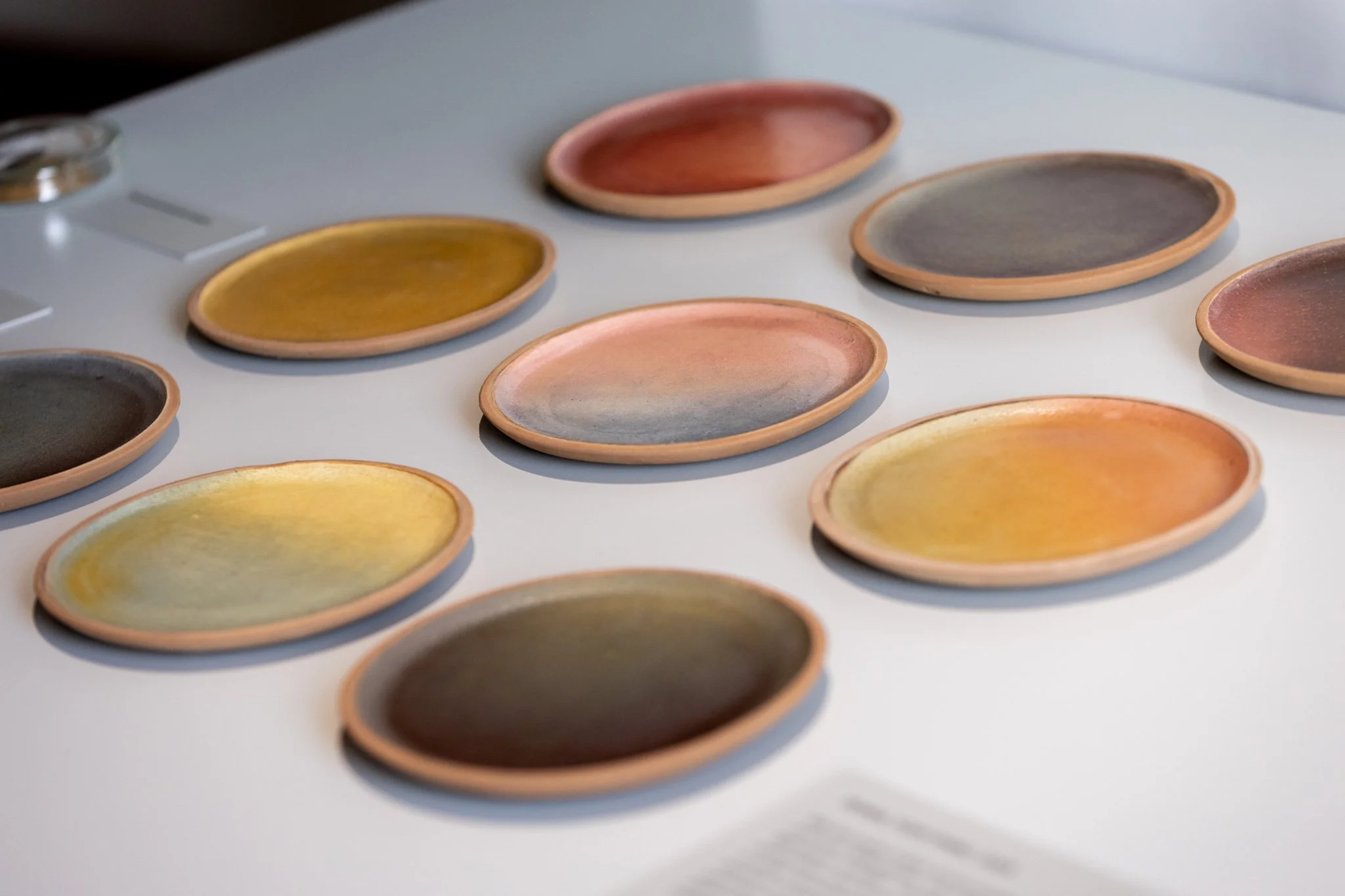

After the question how many cups we actually need, comes the next; How to produce ceramics without exploiting people and depleting the earth's resources? These pioneers show their perspectives and approaches which lead to their experiments and innovations.

For example, by firing the clay less or not at all, CO2 emissions are significantly reduced. And what if residual material is no longer waste, but raw material? Or perhaps we won't need to mine raw materials at all if we can recycle ceramics endlessly?

See the inspiring and beautiful works on display by Hannah Rose Whittle and Benedetta Pompili of the Rijksakademie Tech Fellowship Programme, Amsterdam; Studio Lotte Douwes, Rotterdam; Fabrikaat, Nijmegen and the Alternative Ceramics Supply, Australia.